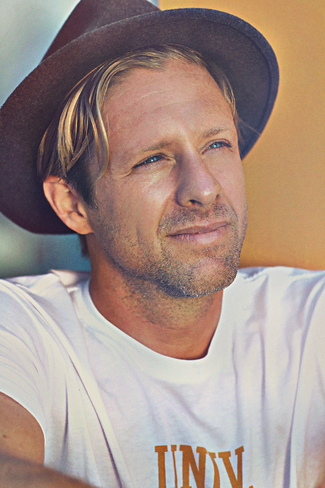

As one of the founding fathers of the multi-platinum alt-rock band Switchfoot, Jon Foreman is one of music’s most recognizable young veterans. But even longtime Switchfoot listeners admire the beloved front man for more than just music. His holistic platform encompasses a passion for philanthropy, his west coast homeland and surfing, and a reflective solo discography, wrestling down the mysteries of his faith alongside fans, not simply in front of them.

Having already released a seasonal EP series—Fall, Winter, Spring and Summer—plus a pair of acoustic-alt-folk records as one-half of Fiction Family, a side collaboration with Nickel Creek‘s Sean Watkins, Foreman’s thoughtful singer-songwriter prose has enlisted a throng of discerning listeners all his own.

Following his serial trend, 2015 introduces a new collection of EPs entitled The Wonderlands. Featuring 24 songs, produced by 24 creatives, divvied up between four EPs—the already-released Sunlight, Shadows and Darkness, with Dawn, releasing later this month—Foreman takes the time to pause and reflect on the unique language of music, and how this melodic speech can help us express our hearts for each other, and for God.

CCM: Twenty-four songs. Twenty-four producers. Help me wrap my head around the motivation behind utilizing so many different people to capture this massive set list of songs?

CCM: Twenty-four songs. Twenty-four producers. Help me wrap my head around the motivation behind utilizing so many different people to capture this massive set list of songs?

Jon Foreman: The question was, “How do you make a record while touring?” I wanted The Wonderlands to be acoustic guitar with lush instrumentation. I can fake playing enough instruments on the road, but I don’t play cello or bass clarinet [Laugh]. I really can’t get that orchestral feel. So, my friend, Chris York, and I came up with the idea of hiring these incredibly talented friends of ours, sending them the songs and they would send us back all the tracks. Cello, piano, choir, whatever.

All these different producers—Andrew [Wessen] from Grouplove, Darren [King] from Mutemath, Taylor [York] from Paramore, Jeff Coffin from Dave Matthews Band—I would send them various stages of a song, and they would send their version of it back.

After the first record I realized I really like a sparring partner. I like someone to hit back with their own musical muscle. I need that. I need somebody else in the ring with me.

CCM: What was the significance behind the number ’24?’

JF: I wanted to create a world with Wonderland, where all these songs would map out this place that wasn’t quite earth. Where you could look back at our planet from this objective position that gives you a little distance. Then the concept of 24-hours of this musical planet came as we were grouping the songs.

CCM: Music is therapeutic. It is an outlet for our feelings—to give feelings to our penmanship, of sorts. These EPs explore the gamut of emotions. How do they help you express what is on your mind and heart?

JF: I feel like melody and music, in general, expresses things I can’t express any other way. Music often tells the truth quicker than words, couple that with social acceptability. It is socially acceptable for me to sing a song about God, girls, sex, doubt, fear, anything, in front of thousands of people, but I would have trouble talking about these issues with my closest friends. It gets to the heart of the matter.

Referring to the idea of writing fantasy, C.S. Lewis said it could, steal past those watchful dragons, of religion. I feel like music does the same thing as a kind of melodic allegory of life.

In music, there’s this idea of tension and release. Periods of doubt, and then resolve. We get to the other side. Sometimes music says those things more clearly than words.

CCM: Music seems to have a universal relatability.

JF: I’ve played shows in Japan, India, South Africa, all over the Philippines, and Malaysia, where people don’t necessarily speak English. And that’s what I sing in, right? [Laughs] Somehow the content of the lyric gets across. It’s crazy to see a bunch of people who don’t speak English singing along perfectly to your song with their hands up in the air, eyes closed. Then you talk to them after the show and they don’t speak English. You realize what a powerful connection music has with the heart.

CCM: I have heard you suggest there is a stark difference between cynicism, of becoming cynical, and being honest and vulnerable. Can you expound on the relationship between becoming honest and music?

JF: I think we get hurt in this life. There are moments of suffering, and some of those suffering moments are at the hands of other human souls. A lot of it takes place in junior high and high school, right? Kids can be ruthless. That doesn’t necessarily stop in adulthood. So we begin to wear these masks, and cover ourselves up for protection.

The problem is these masks destroy our authenticity. They destroy our ability to be completely immersed in the moment, to be present in the present. As much as they keep out pain, they also keep out joy.

So, I think cynicism is a response to the pain. Every cynic was a dreamer once, but cynicism seems like a good knee-jerk reaction to protect. Sometimes it takes a song or a reminder to get over the walls we’ve built. Beauty does that so well. I see the eyes of my daughter and all my walls are broken down. I’m a kid again. Music can do the same thing. An incredible painting, a picture, a phone call from a friend can take us there. These are the reminders of a story bigger than the pain. Sometimes that’s what we need. I need it, for sure.

CCM: The verses of these songs delve into the deep mystery of life’s unknowns, and seem to come to terms, or become comfortable with mystery at the same time. It feels like a coming of age for you spiritually speaking. Is that true?

CCM: The verses of these songs delve into the deep mystery of life’s unknowns, and seem to come to terms, or become comfortable with mystery at the same time. It feels like a coming of age for you spiritually speaking. Is that true?

JF: Hopefully. The moment God becomes something we can write down on a piece of paper, put in our back pocket and say, “I possess,” we almost have a false god in our back pocket. He’s going to be bigger than any kind of theorem we can put Him in.

If we disallow the mystery, especially in our theology, but also in our own personal lives, then we are forcing this odd dichotomy where we aren’t allowing ourselves to be fully human. To be human is to be immersed in the mystery. To be soul, and body. To be in the present with an awareness for the future and the past, with an understanding that someday this body will no longer be living.

The moment we cut these mysteries up and make them less-than, we’ve done ourselves, and our children a disservice. You know?

CCM: Where you live in California, you are founding a music school where underprivileged teens can receive music lessons. What inspired this?

JF: A desire to see the world change was the initial impetus for all of my crazy projects. You are first aware of a problem. The problem, at least in California, is all the music programs are being cut—art and theatre programs as well. So I thought, “Maybe music is being cut because music it’s no longer needed for a child’s education.” Then I did the research, and music is crucial for better test scores in art, math and literature. And itís also crucial for self-esteem, holding a job and higher education. So then the question becomes, “What are we going to do about it?”

As musicians, we care more about music than anyone. So if we’re not going to do something, then no one’s going to do anything. That’s where the initial thrust came from. We’re hoping to open it this fall.

Listen Live

Listen Live

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.